I’ve maintained the jsdom open-source project for over ten years. It’s essentially a partial implementation of a web browser in Node.js, including complexities like resource loading, styling and scripting, and Web IDL bindings. Along the way I’ve been privileged to invite several talented engineers onto the maintainers team, as they took time from their lives to significantly improve the project.

For a long time, working on jsdom was a leisure activity. I’d get home from my day job working on web standards and the ~35 million LOC Chrome web browser at Google, and then I’d unwind by implementing some web standards and fixing some bug reports in my scrappy ~1 million LOC jsdom codebase.

Some time around COVID, my commitment to jsdom, and open-source maintenance in general, waned. Without the mental reset of walking home and switching computers, coding during evenings and weekends no longer sparked joy. So I retreated to a more passive role, attempting to be responsive to issues and pull requests, but not actively improving the library.

It didn’t help that the jsdom codebase was running out of low-hanging fruit. The most-reported issues were symptoms of fundamentally broken or outdated subsystems. Things like resource loading, CSS parsing and the CSS object model, and selectors. The most popular feature requests were similarly daunting: implementing the Fetch API, or all of the SVG element classes, or JavaScript module support. The web platform had kept growing at the pace of Apple, Google, and Mozilla, whereas my spare time had not.

And with the benefit of distance, I had started to realize that the jsdom project was … kind of pointless anyway. Why use a Node.js reimplementation of a web browser, when you could instead drive a real headless web browser? Sure, jsdom is a little more lightweight. Sure, it’s in-process instead of out-of-process. But do you really want to pay the substantial correctness tax of using our off-brand incomplete web platform implementation, just for those benefits? It certainly seems like a bad idea to do so for testing, where correctness is paramount!

In the end, if you want something minimal for scraping or DOM manipulation in Node.js, you can use cheerio. If you want to interface with the actual web, including complexities like layout and navigation, you can use Puppeteer. It’s hard to believe there’s a large market for jsdom’s niche: an obsessively spec-compliant, script-executing, but very much partial implementation of the web platform.

I still have a soft spot in my heart for jsdom, which maintains an inexplicable popularity at 48 million weekly downloads. (Compare to React’s 80 million.) When I was asked to participate in an AI coding productivity study, I leaped at the chance to fix a backlog of jsdom issues. And recently, a new contributor has | appeared and thrown themselves into fixing our selector and CSS subsystems. I’m doing my best to stay responsive and get their diligent work released to the world. But if pressed, I would say the project is in maintenance mode.

After we moved to Japan, my wife and I tried snowboarding. She took to it, but I … did not. What can I say? A gear-heavy, high-learning-curve, single-season, somewhat-dangerous, adverse-weather–centric sport is just not where I want to invest my free time.

But a lot of our friends’ social lives revolve around snow trips during the winter. So recently I’ve been tagging along as the group heads off to snow towns. I explore the café scene during the day while everyone else is sliding down the mountain. And so it is that I find myself in a cozy bakery in Nozawa Onsen, staring at the Claude Code terminal and wondering what I should work on next.

Me making my way to the hotel lounge for some solid coding time.

Me making my way to the hotel lounge for some solid coding time.

Well, there was that one jsdom bug. The one that got filed in 2019, and immediately made me embarrassed about how I’d gotten such a fundamental thing wrong. I always told myself I’d fix it “next weekend”, keeping it on my tasks list for far too many years, before facing the reality that I wasn’t going to prioritize it. But maybe … with the power of Claude … now was the time?

The next three weeks flew by in a blur. I definitely caught the Claude Code psychosis. My previous Cursor-assisted work on the jsdom bug backlog felt productive; my Claude Code-assisted Windows utility program was a fun diversion. But ripping the guts out of jsdom’s resource loading subsystem and replacing them wholesale? Addictive.

It’s hard to describe why. But from an ethnographic perspective, I think it’s important to try.

With every prompt, Claude would delight me with how much progress it made. But there would always be more threads to follow up on—more value I could add. I would review Claude’s code and suggest simplifications. Or I’d realize that we were starting to touch another area of the codebase, which had its own problems, and couldn’t we go and refactor that part too? Or we’d just burn through the list of failing tests, often in a two-steps-forward-one-step-back fashion where our fix for one would improve the architecture while causing a small regression elsewhere.

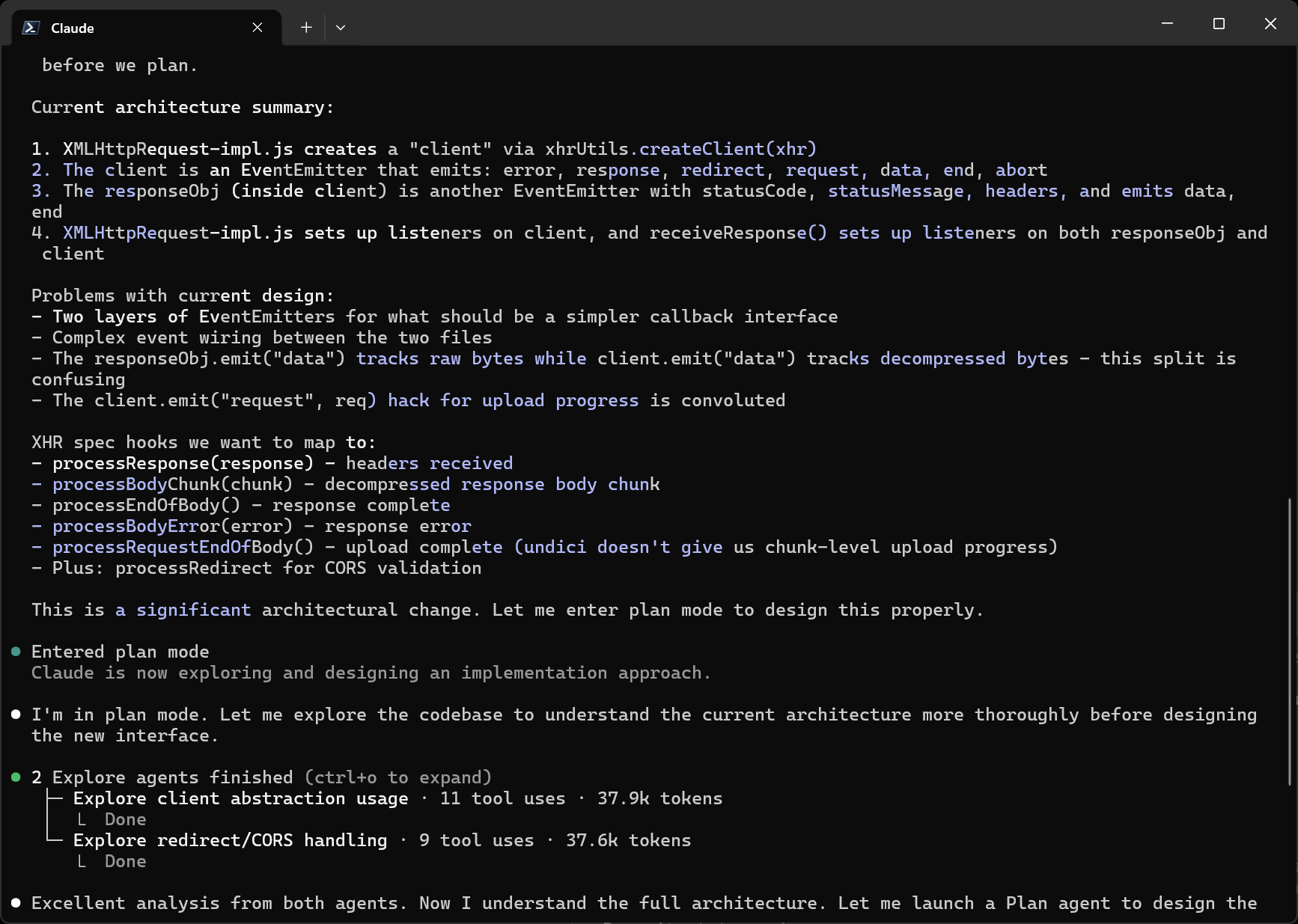

Claude and its subagents go to town on the

Claude and its subagents go to town on the XMLHttpRequest part of the jsdom codebase.

I found myself reopening my laptop during any spare interval. Before we went out for dinner, I’d spend ten minutes writing up a big prompt so I could get the thrill of seeing what Claude produced while I was gone. I daydreamed about setting up one of those Claude Code-from-your-phone setups people are advertising on X. (But I didn’t pull the trigger, because it’s important to have boundaries and not become a phone zombie.)

This time around, the intensity of the work pulled me deeper into the agentic coding ecosystem. I started using Git worktrees, so I could factor out smaller PRs from the main work and land them independently. I added an AGENTS.md once I had enough experience to know what it should say. I tried Codex CLI, and verified the rumors that it can work autonomously and churn out tons of code that passes a given test suite—as long as you’re willing to babysit it through a shit-ton of pointless permissions escalations. Inspired by Christoph, I briefly experimented with Codex Web, before deciding it was too lazy for my needs.

After we completed the first pass at a rewrite in 5 days, I realized I wanted to go further. So I squashed those 43 commits into one, and started another branch. 77 commits and 8 days later, that was ready. I let GitHub Copilot and GPT 5.2 Codex have a crack at reviewing it—they found some good issues!—and finally merged into main. jsdom v28.0.0 has the results.

And part of me is very happy with the end result. I think the new API, and the code behind it, is beautiful. I’m proud of how I engaged with Claude and the other agents, double-checking every line of code and constantly iterating toward the simplest, most general solution. We closed 5 high-difficulty open issues, one dating back to 2016. I engaged with the authors of Undici, the library underlying Node.js’s fetching infrastructure, and reported several bugs. Working on jsdom is fun again; maybe I can tackle all those other fundamental issues next!

But … wait. Should I?

Claude cannot magically make jsdom into a valuable project. On the one hand, fixing a bug dating back to 2016 is gratifying. On the other hand, that bug’s been open since 2016, with only 6 upvotes.

I agree with the general sentiment that the Opus 4.5 / Codex 5.2 generation represents a step change. That although back in ye olde July 2025, AI agents on average slowed down experienced developers working on large codebases, these days they’re probably a speedup.

But they haven’t solved the need to plan and prioritize and project-manage. And by making even low-priority work addictive and engaging, there’s a real possibility that programmers will be burning through their backlog of bugs and refactors, instead of just executing on top priorities faster. Put another way, while AI agents might make it possible for a disciplined team to ship in half the time, a less-disciplined team might ship following the original schedule, with beautifully-extensible internal architecture, all P3 bugs fixed, and several side projects and supporting tools spun up as part of the effort.

I’m not aiming for a lesson here. More of an observation. Unlike Sean, whose blog is full of great takes on how to add value to a software engineering org, I’m retired. If I want to spend my time polishing an open-source codebase to within a centimeter of its life, that’s my choice. But am I doing that because it’s part of living my upon-reflection best life? Or am I doing it because I’ve reached a point with my Japanese flashcard project where I need to do more user testing and evals and design work, and that’s less fun than diving into the familiar jsdom codebase with my little agent buddy?